I have a window fetish. There, I’ve said it. Mullions or muntins* of different widths make my hair stand on end; they let the building down, its facade a jumble. Simply put, both God and the Devil are in the detail … and detail is where stories can be told.

I have a window fetish. There, I’ve said it. Mullions or muntins* of different widths make my hair stand on end; they let the building down, its facade a jumble. Simply put, both God and the Devil are in the detail … and detail is where stories can be told.

Buildings that combine to create our urban landscape can provide pleasure that will soar or crash during a ride through London streets. When observing architecture both old and new from my trusty moped, the heart can leap at a triumph, sink at lazy building design and twist with irritation when faced with something that should never have passed planning. But the greatest pleasure lies in spying a detail that hints at the story behind the building, its context, intent and aspiration.

There is something wonderful about a building façade that is proud to address the world around it. Brick has made a huge comeback in recent years, although the craftsman bricklayer is unlikely to enthuse over the faced panels often used to create the illusion of a traditional brick wall. Some architects reference the building’s historic context by specifying a material or finish that speaks of its past; a favourite of mine is the Turnmill Building, faced with bespoke bricks designed as an homage to the nature and form of Clerkenwell’s warehouses.

The Peabody Trust was once known for the design of beautifully detailed, elegant estates that spoke to their location and provided not only function but respect to occupants. Its earliest developments considered the health of tenants, taking into account basic requirements for natural ventilation as well as spaces for children to play, and for the elderly to perambulate and socialise. The older Peabody Estate embraced a healthy mix of adults, children, singles, couples and families who lived and played side by side, unlike much of today’s silo developments designed specifically for The Retired, The Professional, The Couple or The Family. Not much society going on there, then.

Speaking of contemporary building design, let’s turn to the pervasive glazed façade, an unedifying solution exemplified neatly by the Lexicon Building on London’s City Road. Here, SOM with Squire and Partners designed a handsome building, each apartment sealed with floor to ceiling glass. Presumably the developer was happy to avoid the expense of window openings or balconies; unsurprisingly, all these high windows feature drawn, full length blinds protecting the occupant from the magnified morning sun beating straight into their home – and the panoramic city views for which they have paid a premium. At launch in 2015 a two-bed apartment here cost a cool £1.4m – a substantial sum for hot, blind home. No story there.

Balconies once offered beauty for those both in and outside a building, their design perhaps giving expression to a plainer façade. From delightfully carved stone or wrought iron coaxed into wonderful designs, even the most modest but carefully crafted balustrade had the capacity to lift the spirits for passers-by. Apartment blocks have become ubiquitous in their design, often ignoring the context or story of their environment. This repetitive architecture is bereft of the creative thought that could transform its presence in the street. The Bagel Factory in Hackney Wick missed a trick: why are there no lovely fat ironwork circles within the balcony frames, to echo not only the building’s lovely brand, but its history too?

Dull grey steel vertical bars proliferate balconies on myriad new-build apartment buildings; worse still is the use of solid glass, denying the smallest pleasure-giving breeze to flow through the enclosed space with not so much as a nod to the history of place or people.

Imagination, art and sculpture has a part to play in the built environment; older buildings feature embellishments that speak of its intent, or they may just bring a playful lift to an otherwise perfunctory function. Riding through London I see gargoyles below gutters, sculpted embellishments around windows, thoughtfully crafted fanlights, a date carved into a lintel, wall or gable. Today that opportunity is missed, most especially in the design of municipal buildings when once the architecture may have spoken of the area’s backstory or hopes and dreams for the future.

Haggerston Baths and Washhouse was built with the best materials that celebrated the area’s brick and tile industry. Intended to engender pride amongst the residents of one of the poorest boroughs in London, this red brick building provided beautifully designed public amenities within, and a compelling exterior enhanced with colonnaded balcony, topped by a cupola with a gilded ship weathervane. Author and local resident Ian Sinclair reports that ships on pub signs and weathervanes confirmed London’s self-confidence as a world port.

Which brings me neatly to finials, embellishments implicit to the Regency overtones of my home town, Brighton. Here, it is as if in commissioning his Pavilion the Prince Regent gave permission for buildings to enjoy themselves, for the architecture that emerged from this period is nothing if not elegantly decorative. Brighton and Hove rooftops are alive with animals, dragons, gargoyles, angels and more simple but ebullient ornamentation. The exuberance of its architecture has surely played a part in the town’s cheeky reputation.

All over the world, craft, art, sculpture, turrets, domes, finials and flourishes celebrate the buildings we come to love and remember. Legacy architecture that speaks not only of the history of surrounding streets but respects and uplifts its residents and workers.

Glass and steel serve a purpose and I’m all for modernism, but it seems that imaginative, humane and creative building design has been “valued” out of contemporary architecture. In these times of uncertainty, of dissatisfaction with the world around us, perhaps developers might think about how to create more artful, spirited context and legacy that can make a real difference.

- Mullion: a heavy vertical or horizontal member between adjoining window units

- Muntin: narrow strips of wood that divide the individual panes of glass in a traditional sash

© Giovanna Forte 2019

I feel a caption competition coming on. Framed by my open thighs, the two women’s faces looked up and laughed.

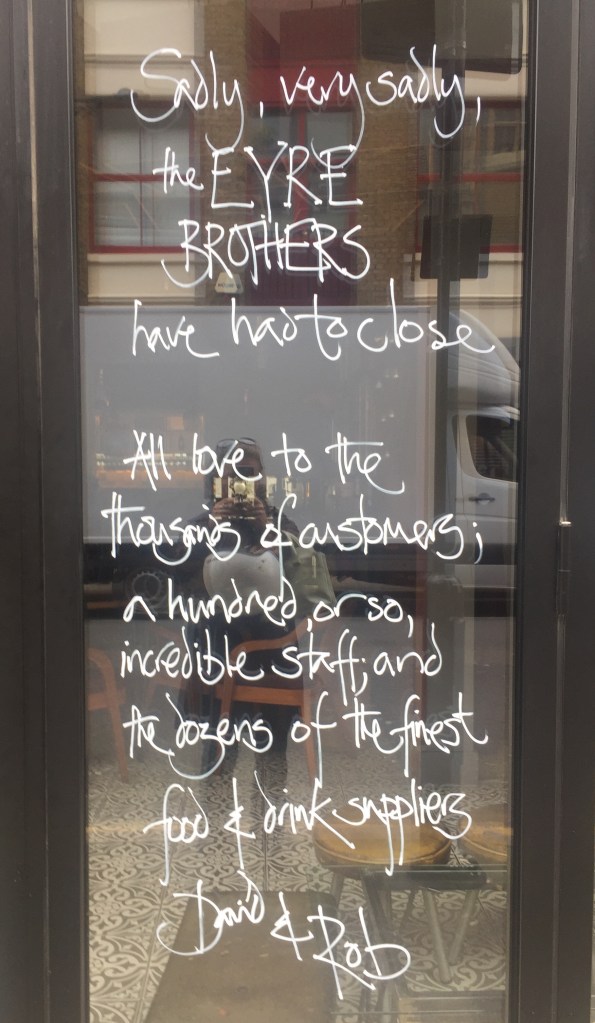

I feel a caption competition coming on. Framed by my open thighs, the two women’s faces looked up and laughed.  Fortewinks’ May post was delivered with little insight as to the Very Difficult Time that was unfolding. Because every now and then the outcome of precipitous events does not become clear until later: this was such an episode.

Fortewinks’ May post was delivered with little insight as to the Very Difficult Time that was unfolding. Because every now and then the outcome of precipitous events does not become clear until later: this was such an episode. Fifty-five is not an insubstantial age but not as old as I hope to be one day – assuming I will remain in fine fettle of course. This year’s birthday celebrations extended to before and beyond the day itself and I bring you now the marvellous and varied shenanigans that have led to this Bank Holiday weekend.

Fifty-five is not an insubstantial age but not as old as I hope to be one day – assuming I will remain in fine fettle of course. This year’s birthday celebrations extended to before and beyond the day itself and I bring you now the marvellous and varied shenanigans that have led to this Bank Holiday weekend.

Hurly burly: life is busy. Rest and relaxation can be hard to come by as one’s mind keeps the plates of work, domestics, love and wellbeing spinning. Meanwhile, against the odds, somehow the body keeps going.

Hurly burly: life is busy. Rest and relaxation can be hard to come by as one’s mind keeps the plates of work, domestics, love and wellbeing spinning. Meanwhile, against the odds, somehow the body keeps going. He proposed the idea with such excitement and enthusiasm that I felt guilty saying no. It just didn’t feel right, didn’t strike the right chord.

He proposed the idea with such excitement and enthusiasm that I felt guilty saying no. It just didn’t feel right, didn’t strike the right chord.

Friday afternoon, a long week behind me I pack up at Forte HQ and consider swinging barside to see who might be around and about for a general unwinding and clinking of a glass or two.

Friday afternoon, a long week behind me I pack up at Forte HQ and consider swinging barside to see who might be around and about for a general unwinding and clinking of a glass or two.